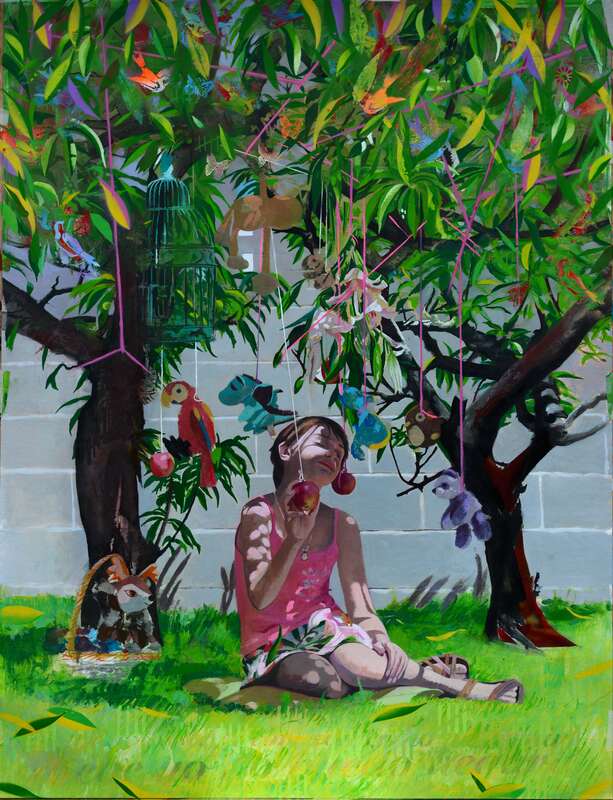

"Memphis Backyard 2020" was purchased as part of the Memphis International Airport Art collection and installed at the new terminal B. "The Art Collection of the Memphis International Airport (MEM) includes a selection of purchased and commissioned works from emerging and established artists who are based in Memphis or connected to our city. These artists represent an ever-evolving arts community that meaningfully contributes to the rich cultural fabric of this city. Whether viewers are enjoying the details of a photograph or taking in an expansive mural, the collection offers an introduction to the many sides of Memphis; for those who call the city home, it is a warm welcome, familiar but never predictable. " from the Urban Art Commission website.

|

Porter-Leath, in partnership with The CLTV and the Memphis Urban Art Commission, put an open call for three artists to create indoor murals, to be located inside the new Porter-Leath University of Memphis Early Childhood Academy in Orange Mound. I was selected as well as the artists Daria Davis and Sarai Payne after a long selection process. All three murals are located inside the “Main St.” lobby area, the murals were painted on polytab and installed at their final destination in January of 2022.

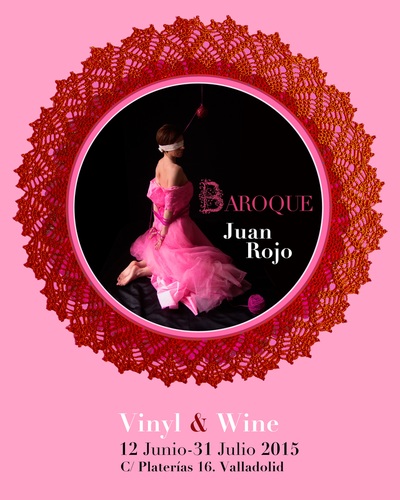

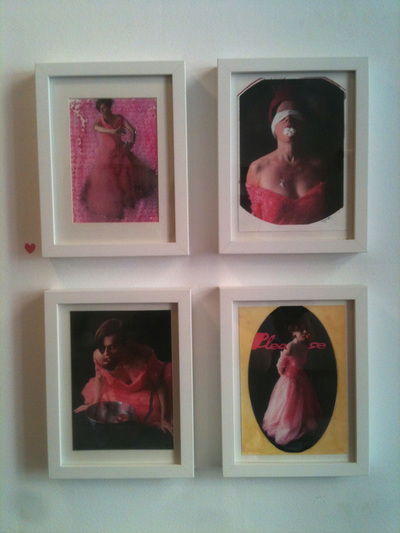

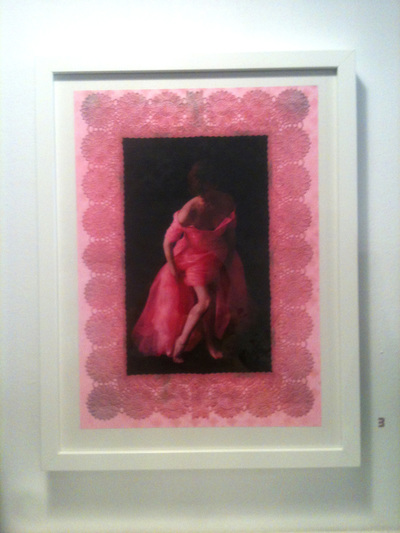

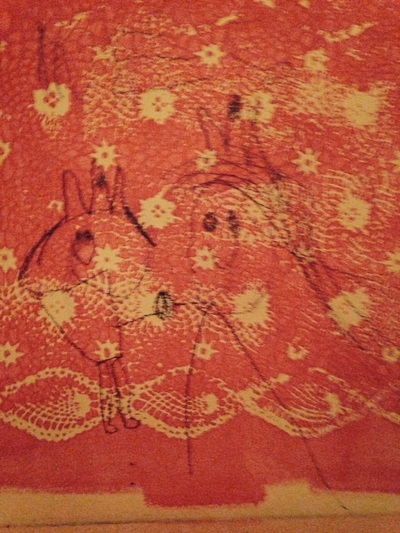

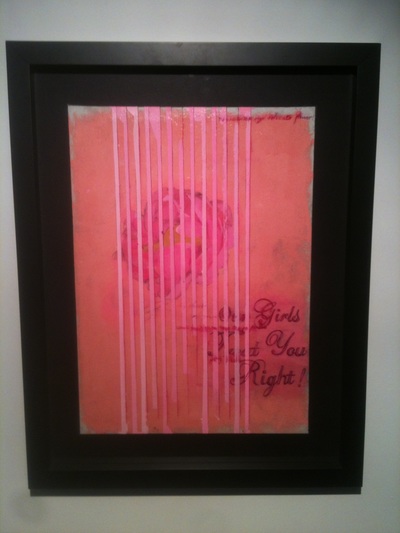

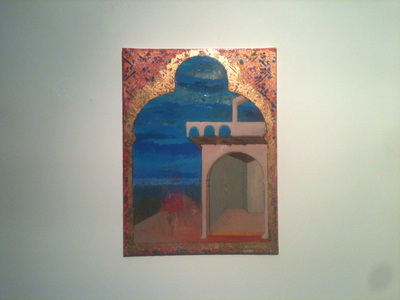

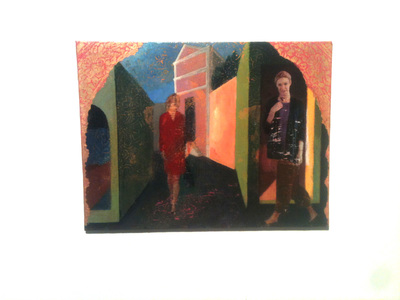

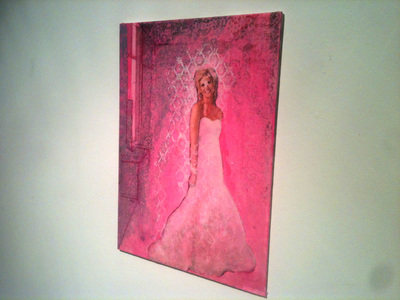

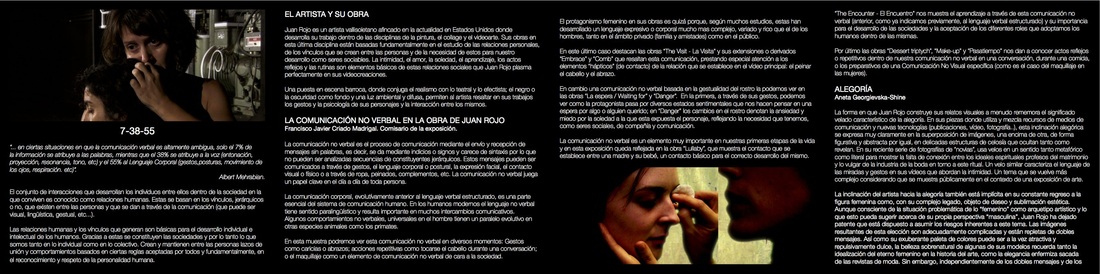

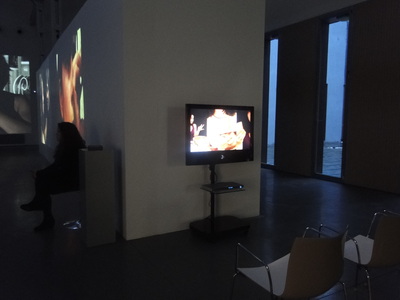

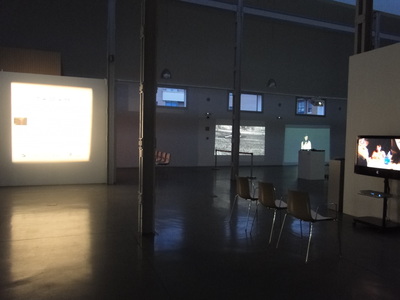

“Pink Room /De Color de Rosa” is a multimedia installation of projected videos, wall painting, and printmaking. The main element of the exhibition is a multichannel projection of videos that depict women performing a Cinderella inspired routine. The performances were recorded in their own houses where I brought a big pink cloth that functioned as a stage curtain. The intense pink color of the videos is the only illumination of the room, bathing the viewer in a warm pink light. This installation interrogates the strategies of the patriarchy and questions the construction of the feminine and all that exists within its confines. At the Art Museum of the University of Memphis, March 14th-July 2nd with opening reception on March 20th from 5pm-7:30pm. The ways in which Juan Rojo constructs his visual narratives often calls to mind the veiling of meaning characteristic of allegory. In his mixed-media pieces, this allegorical bent is most clearly expressed in the layering of images on top of one another, figurative and abstract alike, into delicate, lattice-like structures that mask as much as they disclose. In a recent series of photographs of “brides,” he uses veils in a literal as well as metaphorical sense to comment on the disconnect between the professed spiritual ideals of marriage and the crassness of the wedding industry built around this ritual. Similar veiling characterizes the language of gazes in gestures in his videos that address intimacy – a theme that becomes even more complex as one considers their public display within the context on an art exhibition. The artist’s inclination towards allegory is also implicit in his consistent return to the female figure as a motif, with its complex legacy as an object of desire and aesthetic sublimation. Though fully aware of the problematic status of the “female” as an artistic archetype and what it may suggest about his own particular “male” perspective, Juan Rojo has made it thoroughly clear that he is willing to take the risks inherent in this subject. The images resulting from his choice are appropriately complicated are replete with double messages. Just as their lush color palette can be both alluring and repulsively sweet, the preternatural beauty of some of his models often calls to mind both the idealization of the eternal feminine in “high” art and the sickening sleekness of the glossy magazines they have been culled from. Yet regardless of these double messages and varied points of origin – for he sometimes works from live models as well – the self-consciousness of these beauties begs the question of the ideal beholder. Are they intended for a male or a female viewer and if so, how might that difference alter their meanings? Do they feed the voyeuristic impulse or undermine it by acknowledging the pleasure they elicit? Ultimately, is the artist indulging in that pleasure himself or engaging in a “feminist” critique of the male gaze, as he has often noted in his own comments on the reasons for his continuous return to the female nude? In most of his compositions, Rojo leaves these questions teasingly unresolved, as if to underscore the complexity of visual signs as construed by the exchange between himself and the object of his gaze, as well as by the ways in which that exchange might be interpreted by different beholders. An equally important thematic concern in Rojo’s work is the relationship between the unique and the mass-produced. This becomes especially important in his practice of appropriation of photographic reproductions, whether from women’s magazines or upscale sales catalogues, and their subsequent manipulation through the application of different techniques whereby an image that begins its life as a multiple becomes a new and unique visual record of an artistic process. Yet again, even as he removes the quality of the mass-produced by transferring, over-painting, partial erasure and camouflage of the original, Rojo is also willing to counter this whole movement towards the unique by photographing or printing the resulting images. Through this second conversion of the unique into the reproducible, the artist reminds us of one of the most unsettling questions of our time: is the instant visual gratification enabled by ever increasing modes of reproduction slowly eliminating the very idea of the icon? Though the artist recognizes this possibility, he keeps returning to images that have historically claimed that status, as if to prove their continuing relevance. Even when his painterly improvisations on classical subjects such as the myth of Danae, or quotations of specific works of art such as Botticelli’s Uffizi Annunciation, remain unnoticed or cause merely the faintest flicker of something familiar, those losses of meaning are more than compensated for by the visual rewards of form and color itself. In a similar way, though his declared challenge to the objectification of the female is obscured at times by the blatant erotic appeal of his models, the restrained yet undeniable aggressiveness of his manipulation of these pin-ups problematizes their pleasure-producing value for the male viewer. The same multiplicity of meanings applies to his videos, which invariably feature female actors in a variety of intimate performances. Like his collages, photo-transfers, and paintings, these moving images create subtly transgressive narratives that question historically-codified stereotypes about the female as a muse, seductress, and object of the male gaze. They are also just as clearly balanced between formal and conceptual concerns. The mind may remain baffled by the artist’s intention, but the eye is nourished by saturated hues and chiaroscuro illumination. Like his paintings and mixed-media pieces, these videos also offer multiple possibilities for interpretation. This open-endedness, combined with his close attention to the visual, gives them coherence as a body of work and allows one to recognize them as just another stage within the artist’s ongoing exploration of the uncertainties of looking, representation, and the veils interposed in between. ANETA GEORGIEVSKA-SHINE teaches art history and theory in the Departments of Art History and Fine Arts, University of Maryland, College Park. Her research focuses on the reception of classical art and literature in the early modern period, as well as inter-pictorial and inter-cultural exchanges. Her publications include two books, Rubens and the Archaeology of Myth: Visual and Poetic Memory (2009), Rubens, Velázquez and the King of Spain (co-authored with Larry Silver, 2014), journal articles, and essays in edited volumes. She has also written numerous catalogue essays and art reviews on modern and contemporary art. |

|